No, Virginia, Tax Cuts Don’t Cause Higher Interest Rates

The Federal government will hand down its 2007-08 Budget next Tuesday facing an all too familiar embarrassment of riches. On a no policy change basis, the 2006-07 underlying cash surplus could easily exceed $16 billion compared to a MYEFO estimate of $11.8 billion, with the 2007-08 surplus likely to be in excess of $10 billion.

The actual surplus will then depend on how the government allocates the surplus among new spending, tax cuts and the Future Fund. The challenge for the government in recent budgets has been to hold the fiscal impulse neutral, by keeping the change in the budget balance broadly steady as a share of GDP, in the face of what would otherwise have been a sharp fiscal contraction brought about by revenue growth that has consistently exceeded previous estimates. This is consistent with the view that fiscal policy should be focused on microeconomic objectives and not demand management, with the latter task being best left to monetary policy.

Among financial market economists, there is nonetheless a widely held view that the government should somehow assist the RBA in its demand management task, by favouring the accumulation of surpluses in the Future Fund over tax cuts to avoid putting upward pressure on inflation and interest rates. The same argument is rarely made against new spending measures, even though ‘crowding out’ is a much more serious problem in relation to new spending than tax cuts.

continue reading

posted on 04 May 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Return of the Perfect Latin American Idiot

Alvaro Vargas Llosa on the Return of the Perfect Latin American Idiot.

posted on 02 May 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Andy Xie Club

Andy ‘These Western People Didn’t Know What They Were Talking About’ Xie is back on the loose:

Xie told Reuters that he plans to set up an “investment club” that would be open only to people he knows. The club would invest in unlisted firms, would have total funds of $200 to $300 million and would be focused solely on China.

“I’m looking for backers who know me, so there’s a trust element involved and that would make decisions much easier,” he added.

Xie—who worked at Morgan Stanley for nine years and spent five years as an economist with the World Bank—resigned from the U.S. investment bank after an email with disparaging comments about Singapore’s economic policy was leaked to the public.

His email was written shortly after the IMF/World Bank meetings in Singapore in September.

Xie declined to elaborate on his departure, but said he was already considering resigning from the bank before then.

He added that he would not join another firm again and does not rule out heading his own fund in future. He sees himself traveling around China, dispensing economic advice.

posted on 02 May 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Efficient Markets

James Hamilton’s recession probability index: 16.9%.

Intrade’s US 2007 recession contract implied probability: 15%.

Who said prediction markets don’t reflect fundamentals?

posted on 28 April 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Too Big to be Left Alone: The European Assault on Hedge Funds

Jurgen Reinhoudt on the European assault on hedge funds.

posted on 26 April 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Don’t Worry About the US Mortgage Market

The Peterson Institute’s Adam Posen, on why developments in the US mortgage market are not a threat to the wider US economy:

The biggest structural change has been the shift to securitized mortgage lending. Close to 60 percent of residential mortgages in the United States now are not kept on the lenders’ books—upon making the loan, the lender or a larger intermediary bundles these with other loans of similar attributes and sells them to investors in the form of a bond or security. As a result, the mortgage lender gets its cash repaid almost immediately. While the risk from mortgage defaults remain in the system, it avoids collecting on the balance sheets of individual banks where, in past real estate busts, it would erode those banks’ capital. That erosion led in turn to banks cutting back lending in their local region, and foreclosing on more mortgages, in hopes of restoring their own solvency. Such credit contraction would then cause significant cutbacks in investment and employment, causing more mortgages to become delinquent in payments, generating a downward cycle. With securitization, losses on delinquent mortgages no longer have direct effects on bank balance sheets, and so their growth impact is limited.

If securitization led to markedly lesser lending standards in the United States when issuing mortgages, those benefits to economic stability would have been partially offset. In theory, such a decline in lending standards might have happened, because those doing the loan evaluations no longer retained the credit risk and so would be less careful. Yet, in practice, three factors seem to have, if anything, improved mortgage lending standards in the United States on net in recent years. First, the financial investors buying securitized mortgages were at least as tough scrutinizing portfolios of loans as individual bankers. Second, greater automation and standardization limited lending on nonmarket criteria. Third, the large players who held and resold the securitized loans are under better regulatory scrutiny themselves, by the Federal Reserve and other regulators, than the smaller mortgage lenders used to be in the United States by smaller, sometimes state-level or politically captured, supervisors.

Incidentally, why is it that one of the few people prepared to defend innovation in the US mortgage market works for a liberal think-tank and is writing in a German newspaper?

posted on 25 April 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Oils Ain’t Oils: The Demise of WTI?

Those who use West Texas Intermediate crude oil for economic forecasting will have probably noticed this:

The mighty Texas crude-oil benchmark—the per-barrel price watched obsessively by the markets and quoted by the media—has diverged so drastically from prices of other grades of crude in recent weeks that some market participants are calling it a “broken benchmark.”

Several factors have combined to push the price of West Texas Intermediate crude oil—used as the basis for the world’s most widely traded energy contract—dollars below other desirable, so-called light sweet crudes.

On Friday, for example, the bellwether oil contract on the New York Mercantile Exchange closed at $63.38 a barrel, nearly 5% less than the $66.49-a-barrel close of North Sea Brent crude, the London benchmark quoted on the ICE Futures exchange.

The disparity, which is partly rooted in structural changes in the energy markets—including how and where oil is produced and shipped—means the standard barrel of oil no longer has a straightforward price…

“Spot WTI crude-oil prices no longer reflect international market dynamics,” Edward Morse, chief energy economist at Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., said in an April 13 report. “Rather, they represent local fundamentals for crude oil in the U.S. mid-continent, putting a question mark over the value of this inland U.S. crude as a world marker for hedging or speculation.”

posted on 23 April 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Real Commodity Prices in the Long-Run

The RBA Bulletin puts the recent boom in commodity prices in long-run perspective. The article includes the following chart of the real gold price. The chart shows that gold makes a poor long-run investment. The best that could be said for gold is that it has held its value over the long-run, but with some very pronounced cycles along the way. The long-run returns to gold are paltry compared to the real returns from equity indices like the S&P 500 over the last century.

posted on 19 April 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Sachs Sucks

Daniel Ben-Ami on Jeffrey Sachs’ Malthusianism:

For Sachs, the key problems facing the world today are rooted in overpopulation: ‘Our generation’s unique challenge is learning to live in an extraordinarily crowded world.’ He argued that the world is ‘bursting at the seams in human terms, in economic terms and in ecological terms’. So for Sachs every human being is, literally and metaphorically, another mouth to feed. The mass of humanity is leaching the planet of its resources and destabilising the world. He grossly underestimates the significance of humans having hands and brains, as well as mouths. Rather than simply consuming resources, humans have the unique ability to produce more than their own subsistence and to transform the environment for the better.

Sachs breaks this supposed problem of overpopulation into three inter-connected challenges. First, there is what he calls the Anthropocene: ‘the idea that for the first time in history the physical systems of the planet…are to an incredible and unrecognised extent under human forcings.’ In other words, for Sachs the fact that humanity now has a significant degree of control over nature, one of the great achievements of progress, is a threat. Rather than having the potential to liberate humanity, he sees scientific and technological advance as destabilising the planet.

posted on 17 April 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Redundant IMF

Adam Lerrick on the IMF’s battle against its own irrelevance:

The institution’s proud lending portfolio that had totaled $100 billion in 2003 has since collapsed. It now stands at $13 billion. Turkey could push that even lower as it dips into a full treasury to pay off a $9 billion balance. The IMF’s lending accounts are shrinking and its income stream drying up…

There was a windfall for the IMF in the decade of bailouts that began with Mexico in 1995. As its loan portfolio tripled and net income ballooned tenfold to $1.2 billion in 2004, there was money enough to pay for another big glass headquarters and a 50% increase in staff to 2,700; to more than double administrative costs to almost $1 billion; and even to poach on the World Bank’s territory of development aid.

Now the Fund is bleeding $200 million to $300 million a year. But there is no talk of retrenchment. Instead, the Fund seeks to become the arbiter of global exchange rates and the arbitrator of economic disputes between nations—grandiose positions that are not needed, wanted nor enforceable in the world economy. And the IMF seeks a new wellspring of funding to support the expansive lifestyle to which it has become accustomed.

A Committee of Eminent Persons was assembled to find the money. Central bankers, among them Alan Greenspan of the U.S. and Jean-Claude Trichet of Europe, joined private-sector leaders Andrew Crockett of JP Morgan and Mohamed El-Erian of Harvard Management. But this assembled brainpower was warned off of the real questions that need to be answered: What is the right role, the right size and the right cost of the IMF?

Instead, the Eminent Persons were shunted off to the IMF’s basement where 103 million ounces in ingots had been left behind from the days of the gold standard. Each ounce, deposited by member countries at $35, is now worth $650, creating a constant temptation for Funders. Selling this resource rather than leaving it in the basement would yield a gain of $60 billion and an investment income of $3 billion a year. The Committee emerged with a proposal to use 13 million ounces, or an eighth of the gold stockpile, to establish an IMF endowment, an independent income stream for the Fund in perpetuity.

The conspiracy theorists at GATA will have a field day with this.

posted on 13 April 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

John Bogle on Investing

Russ Roberts interviews Vanguard founder John Bogle on his book, The Little Book of Common Sense Investing: The Only Way to Guarantee Your Fair Share of Stock Market Returns (Little Book Big Profits).

posted on 12 April 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Market’s US Slowdown Fixation

David Malpass highlights the misplaced concerns about a slow-down in the US economy following the March employment report:

The U.S. continues to be the biggest contributor to global growth. We grew as fast in 2006 as in 2005, over 3% real growth on a $13 trillion base, with small businesses making up for the slowdown in U.S. homebuilding and auto production. The “weak” U.S. 2006 fourth quarter showed 2.5% real growth, with the just-ended January-March quarter nearly as fast. Using Friday’s data, man-hours worked in the first quarter grew 1.5% at an annual rate, with productivity growth, though diminished, expected to add another 1% or so. Big business spending on equipment and software has been sluggish, but the impact on GDP may not be as large as expected.

Several factors still contribute to a deep underestimate of the U.S. economy and shade the global outlook. Monetary policy should be measured by the level of interest rates, not the number of Fed increases from 1%. Housing is a small part of job and economic growth (about 4%). Rather than triggering a recession, the sector is merely returning to normal after the 2004-2005 construction boom. The trade deficit, also not a recession trigger, is matched by a capital account surplus, providing an extra source of inexpensive funding for U.S. growth and investment…

The strong labor report should caution those counting on moderations in U.S. growth and inflation to allow U.S. interest rate cuts. In addition to a weak dollar, the related increase in inflation, and high levels of global liquidity, monetary policy is facing a lower-than-expected unemployment rate even as labor-force growth is set to slow further due to demographics. While low unemployment doesn’t cause inflation—it often increases productivity and output, holding prices down—the Fed will probably factor the new jobs report into its thinking on the economy’s growth relative to its potential, still a factor in its interest rate decisions. The theory is that growth is above potential, and possibly inflationary, if it is pushing the unemployment rate down.

The declining unemployment rate is great news for living standards, but is a stiff challenge to the market’s fixation on slowdown theories and a softening of the Fed’s monetary policy.

Look for a similarly strong Australian March employment report this week.

posted on 10 April 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Stock Market Booms and Monetary Policy: The Strange Resilience of Austrian Business Cycle Theory

We have previously noted the popularity of the Austrian theory of the business cycle as a stylised account of the role of monetary policy in the economy and asset price determination, not least among those who otherwise have little sympathy for the Austrian tradition. The popular appeal of this stylised account is curious, given that it lacks even an approximate fit with the data, as Bordo and Wheelock suggest:

Our review of earlier stock market booms in the United States and nine other developed countries during the 20th century indicates that the patterns observed during the U.S. boom of 1994-2000 were similar to those of earlier booms. Stock market booms typically arose when output growth exceeded its long-run average and when inflation was below its long-run average. There were, however, exceptions. Notably, we find that across all post-1970 booms the median growth rates of real GDP and productivity did not substantially exceed their long-run averages. We find less variation in the association of booms with low inflation than we do in the association of booms with rapid output or productivity growth. Further, we find that both nominal and real money stock growth were typically below average during booms, suggesting that booms did not result from excessive liquidity.

Posen has reached similar conclusions, based on IMF survey evidence:

Monetary ease is neither necessary nor sufficient to produce bubbles. There have been 48 periods of sustained monetary easing in the 15 main industrial countries since 1970, as measured by M3 growth or ultra-low real interest rates, and only 17 of them resulted in asset price booms. At the same time, only one-third of the booms identified by the IMF were preceded or accompanied by monetary ease. If one looks at ease as measured by interest rates, there are essentially no cases where booms were preceded or accompanied by monetary ease. Bubbles are made in financial markets, not in central banks.

Bubbles are rarely followed by either deflation or further bubbles. The dangerousness of bubbles is taken for granted. According to the received wisdom, either they put a lasting burden on investment and prices when they burst or, worse, they lead to follow-on bubbles that build up a bigger collapse. Yet fully three-quarters of the asset price booms had no follow-on bubbles after their busts, and fewer than one in 10 busts led to periods of consumer price deflation.

This cross-national evidence is consistent with economic historians’ assessments of the US experience. Among the many booms, panics, and busts in the 19th and 20th centuries, only those accompanied by banking problems had negative consequences lasting beyond a few quarters. Bubbles can pop with limited macroeconomic impact, and usually do.

The lack of empirical support for the Austrian theory of the business cycle suggests that its main function is to serve as a comforting narrative for those who are troubled by economic and financial developments they cannot otherwise comprehend.

posted on 05 April 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

Losing Money with Steve Hanke

Steve Hanke may have a fetish for fixed exchange rate regimes, but he is not averse to offering Forbes readers free advice on playing foreign exchange markets. Hanke’s fundamental analysis seems to consist of little more than ritual incantations of Austrian business cycle theory, coupled with the traditional promise of the hell-fire preacher that the day of reckoning is nigh.

More specifically, Hanke recommends betting on an unwinding of yen carry trades:

In preparing for a coming storm investors should anticipate further unwinding of yen carry trades and a significant appreciation of the yen. One way to play this is to purchase out-of-the-money call options on the yen traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. I recommend a December call at a strike price of 90.

Anticipating an eventual reversal of Swiss franc carry trades, and a sharp appreciation of the Swissie, I recommended (Sept. 4, 2006) selling a Euro/Swiss futures contract. At present the position is losing 2%. Relax and continue to hold it.

Since the ECB and SNB have been moving interest rates more or less in lock-step since the end of 2005, EUR-CHF is a strange choice to trade the carry trade in either direction, even if one thinks CHF is undervalued. But putting that aside, the preoccupation with the potential for an unwinding of carry trades ignores the fact that these trades have a firm basis in fundamentals, namely real interest rate differentials. Betting on a carry trade unwind is a bet against the fundamentals that drive it. While de-leveraging could give rise to a larger carry trade unwind that would be warranted by changed fundamentals, the extent of the carry trade has been greatly overstated relative to total market turnover. Even if one believes in a ‘coming storm’ for the US economy, betting on a rise in the yen is an odd way to play it, unless you think the US can have a recession, without taking the rest of the world with it.

posted on 03 April 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Doomsday in the Fever Swamp

Just in time for April Fool’s Day, Time magazine profiles The Armageddon Gang. As the article notes, their ‘stark, almost Puritan way of looking at the world… has been out of step with economic reality for the past quarter-century.’

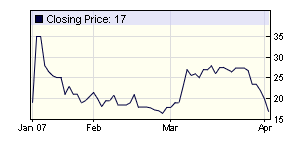

Meanwhile, Intrade’s US 2007 recession contract is in the grip of a bear market of its own:

posted on 02 April 2007 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Page 39 of 45 pages ‹ First < 37 38 39 40 41 > Last ›

|